Difference between revisions of "Tutorial: Basic Orbiting (Technical)"

Leoshnoire (talk | contribs) (Removed irrelevant 3-body equations from page header) |

Leoshnoire (talk | contribs) (→Stabilizing your orbit: Added hand calculation of orbital speed) |

||

| Line 9: | Line 9: | ||

There are a number of third-party calculators available which can crunch the numbers and tell you your eccentricity, as well as provide the speeds required to circularize your orbit at your current (or future) altitude. Whether you calculate your orbits by hand, or use a third party app, the general procedures are still the same and are given below: | There are a number of third-party calculators available which can crunch the numbers and tell you your eccentricity, as well as provide the speeds required to circularize your orbit at your current (or future) altitude. Whether you calculate your orbits by hand, or use a third party app, the general procedures are still the same and are given below: | ||

| − | First, in order to get into a nice, round orbit, you need to determine how fast to go. | + | First, in order to get into a nice, round orbit, you need to determine how fast to go. The mathematical basis for orbital speed is determined from your current distance from your central body (<math>r</math>), your average distance from your central body (<math>a</math>), and the mass of the central body itself (<math>M</math>). These may be use to find the speed at an orbit around any body using the relation |

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | <math>v = \sqrt{GM(\frac{2}{r}-\frac{1}{a})}</math> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | , where <math>G</math> is the gravitational constant <math>6.67384*10^-11</math>. Keep in mind that distances to the central body must account not only for altitude but also for the radius (<math>R</math>) of whatever body you are orbiting. The exact values of <math>M</math> and <math>R</math> may be found on their respective pages. | ||

| + | Returning to our case, the higher your orbit, the less gravity you'll feel from Kerbin, so the slower you'll need to go to be in a circular orbit. Determine the proper speed for your altitude at apoapsis or periapsis either by hand, by calculator, or by table. You'll probably want to watch your altimiter as you near one of the critical points, remember the altitude, determine your desired speed, and make the correction on your next pass. If you want to "round out" your orbit from apoapsis, you need to speed up to avoid falling back down to periapsis. Point your craft in the exact direction of travel (use the green circular indicator on the gimbal to line up), and apply thrust until you've gained enough speed. To round out an orbit from periapsis, you need to slow down to avoid climbing back up to apoapsis. Point your craft in the opposite direction of travel (indicated on the gimbal by a green circle with an "X" through it), and apply thrust until you have slowed to the speed indicated by the table. You should then be in an orbit that is very close to circular! Depending on how eccentric your initial orbit was, you may need to make a large correction on your first pass followed by a small correction on a subsequent pass to get very stable. | ||

If you have version 0.11 or better, adding a set of [[RCS]] thrusters to your craft can help make minute adjustments to an orbit easier. Version 0.11 also allows you to see the current trajectory (and read periapsis and apoapsis altitudes) by switching to the [[Map view]] (M key) | If you have version 0.11 or better, adding a set of [[RCS]] thrusters to your craft can help make minute adjustments to an orbit easier. Version 0.11 also allows you to see the current trajectory (and read periapsis and apoapsis altitudes) by switching to the [[Map view]] (M key) | ||

Revision as of 03:01, 5 January 2014

Getting into space is relatively easy, but staying there without drifting endlessly into space or falling back down to Kerbin can be challenging. This tutorial will teach you how to get into and remain in orbit, how to adjust your orbit to be circular or elliptical, and how to adjust to a higher or lower orbit.

Contents

Stabilizing your orbit

During each orbit, your craft will reach maximum altitude, called apoapsis, and on the opposite side of the planet, it will reach minimum altitude, called periapsis. At both apoapsis and periapsis, your vertical speed will be zero. These points are the easiest points to make orbital corrections, because you can easily determine how fast to go when your vertical speed is zero. Note: The relative difference between your orbit's apoapsis and periapsis is called its eccentricity. Orbits that are exactly circular have zero eccentricity, and highly "flattened-out" orbits have eccentricity close to 1.

There are a number of third-party calculators available which can crunch the numbers and tell you your eccentricity, as well as provide the speeds required to circularize your orbit at your current (or future) altitude. Whether you calculate your orbits by hand, or use a third party app, the general procedures are still the same and are given below:

First, in order to get into a nice, round orbit, you need to determine how fast to go. The mathematical basis for orbital speed is determined from your current distance from your central body (), your average distance from your central body (), and the mass of the central body itself (). These may be use to find the speed at an orbit around any body using the relation

, where is the gravitational constant . Keep in mind that distances to the central body must account not only for altitude but also for the radius () of whatever body you are orbiting. The exact values of and may be found on their respective pages.

Returning to our case, the higher your orbit, the less gravity you'll feel from Kerbin, so the slower you'll need to go to be in a circular orbit. Determine the proper speed for your altitude at apoapsis or periapsis either by hand, by calculator, or by table. You'll probably want to watch your altimiter as you near one of the critical points, remember the altitude, determine your desired speed, and make the correction on your next pass. If you want to "round out" your orbit from apoapsis, you need to speed up to avoid falling back down to periapsis. Point your craft in the exact direction of travel (use the green circular indicator on the gimbal to line up), and apply thrust until you've gained enough speed. To round out an orbit from periapsis, you need to slow down to avoid climbing back up to apoapsis. Point your craft in the opposite direction of travel (indicated on the gimbal by a green circle with an "X" through it), and apply thrust until you have slowed to the speed indicated by the table. You should then be in an orbit that is very close to circular! Depending on how eccentric your initial orbit was, you may need to make a large correction on your first pass followed by a small correction on a subsequent pass to get very stable.

If you have version 0.11 or better, adding a set of RCS thrusters to your craft can help make minute adjustments to an orbit easier. Version 0.11 also allows you to see the current trajectory (and read periapsis and apoapsis altitudes) by switching to the Map view (M key)

Transfer Orbits

The most efficient way to transfer from a lower circular orbit to a higher circular orbit (or vice-versa) is to use an elliptical transfer orbit, also known as a Hohmann transfer orbit. To transfer, we make the periapsis of the elliptical orbit the same as the radius of the lower orbit, and the apoapsis of the elliptical orbit the same as the radius of the higher orbit. If you are going from low to high, you make a burn in the direction of travel to elongate your orbit. You will climb in altitude as you travel around the planet to the apoapsis of your transfer orbit. Then, make a second burn to round out the new, higher orbit (as described above). To go from high to low, do the opposite: Burn in the opposite direction of travel, then fall down to the periapsis of your transfer orbit, and make a second burn to round out the lower orbit (again in the opposite direction of travel).

Target Speed

The key to transfer orbits is figuring out how much speed to add or subtract to reach a desired new orbital altitude. To do this, use the formula below to determine the target velocity for your initial burn:

In this formula, rl and rh are the radii of the lower and higher orbits, respectively, and ri is the radius of the initial orbit. If you are transferring to a higher orbit, ri will be equal to rl, and v will be faster than your current speed, so burn in the direction of travel to reach v. If you are transferring to a lower orbit, ri will be equal to rh, and v will be slower than your current speed, so burn in the opposite direction to reach v. Remember, v is the target speed for your initial burn that puts you into the elliptical transfer orbit. Once you reach your new orbital altitude, you need to make a second burn to round out your orbit, using the same technique described in the stabilizing your orbit section.

Details of where this formula comes from are in the technical section below. When using this formula, take care to remember that the radius of an orbit is equal to the orbital altitude plus Kerbin's radius (600 000 m).

De-orbiting

The most efficient way to de-orbit from any altitude is to initiate a transfer orbit with a periapsis below 70000 m, the edge of Kerbin's atmosphere. Note that the upper atmosphere is very thin so if you do not want to wait for several orbits of aerobraking, aim for under 35000 m and thicker air. As you approach periapsis, the atmospheric drag will start to slow your craft and eventually it can no longer maintain orbit.

R code snippet for planning Hohmann transfer

hohmann <- function(from_alt,to_alt){

# provides information needed to perform

# a hohmann transfer from a circular ortbit

# at from_alt (km) to a circular orbit at to_alt (km)

mu <- 3530.394 # Gravitational parameter (km^3/s^2)

R <- 600 # Kerbin radius (km)

r1 <- from_alt+R # radius 1 (km)

r2 <- to_alt+R # radius 2 (km)

vc1 <- sqrt(mu/r1) # circular orbit velocity 1 (km/s)

vc2 <- sqrt(mu/r2) # circular orbit velocity 2 (km/s)

a <- (r1+r2)/2 # semi-major axis of transfer orbit (km)

T <- 2*pi*sqrt((a^3)/mu) # period of transfer orbit (s)

dv1 <- (sqrt(r2/a)-1)*vc1 # delta v1 (km/s)

dv2 <- (1-sqrt(r1/a))*vc2 # delta v2 (km/s)

b1 <- list(from=vc1,to=vc1+dv1) # burn one from-to velocities (km/s)

t <- T/2 # time between burns (s)

b2 <- list(from=vc2+dv2,to=vc2) # burn two from-to velocities (km/s)

out <- list(from_alt=from_alt,b1=b1,t=t,b2=b2,to_alt=to_alt)

return(out)}

Example usage

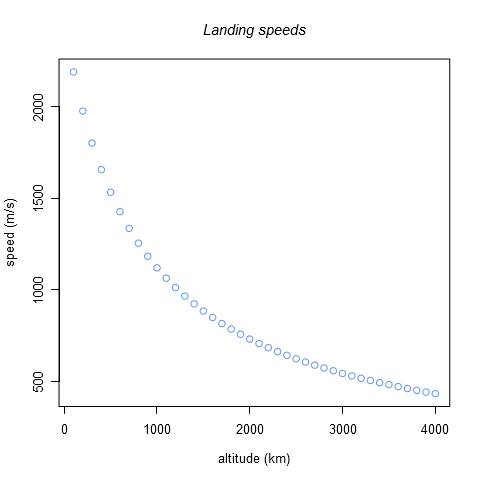

Produce a graph showing the speeds need to transfer from a range of circular orbit altitudes into a landing orbit.

plot(100*1:40,1000*hohmann(100*1:40,34)$b1$to,main="Landing speeds",xlab="altitude (km)",ylab="speed (m/s)")

R project Link[1]

Transfer Orbits

Coming soon!

Orbital Table

Note: The atmosphere previously had a sharp cutoff at 34.5 km, but now extends to approximately 68 km. Below this altitude, your orbit will gradually decay. The decay becomes quite rapid below about 45 km. The orbital parameters below 68 km are provided for reference, but understand that you will not be able to maintain these orbits without regular corrections to counteract the atmospheric drag.

| Altitude (m) | Horizontal Speed (m/s) | Orbital Period (min) |

|---|---|---|

| 40000 | 2348.7 | 28.54 |

| 50000 | 2330.6 | 29.21 |

| 60000 | 2312.8 | 29.88 |

| 70000 | 2295.5 | 30.56 |

| 80000 | 2278.6 | 31.25 |

| 85000 | 2270.3 | 31.60 |

| 90000 | 2262.0 | 31.94 |

| 100000 | 2245.8 | 32.64 |

| 110000 | 2229.9 | 33.34 |

| 120000 | 2214.4 | 34.05 |

| 130000 | 2199.2 | 34.76 |

| 140000 | 2184.3 | 35.48 |

| 150000 | 2169.6 | 36.20 |

| 160000 | 2155.3 | 36.93 |

| 170000 | 2141.3 | 37.66 |

| 180000 | 2127.5 | 38.39 |

| 190000 | 2114.0 | 39.13 |

| 200000 | 2100.7 | 39.88 |

| 210000 | 2087.7 | 40.63 |

| 220000 | 2075.0 | 41.38 |

| 230000 | 2062.4 | 42.14 |

| 240000 | 2050.1 | 42.91 |

| 250000 | 2038.0 | 43.68 |

| 260000 | 2026.1 | 44.45 |

| 270000 | 2014.5 | 45.23 |

| 280000 | 2003.0 | 46.01 |

| 290000 | 1991.7 | 46.79 |

| 300000 | 1980.6 | 47.59 |

| 310000 | 1969.7 | 48.38 |

| 320000 | 1959.0 | 49.18 |

| 330000 | 1948.4 | 49.98 |

| 340000 | 1938.0 | 50.79 |

| 350000 | 1927.8 | 51.61 |

| 360000 | 1917.7 | 52.42 |

| 370000 | 1907.8 | 53.24 |

| 380000 | 1898.0 | 54.07 |

| 390000 | 1888.4 | 54.90 |

| 400000 | 1879.0 | 55.73 |

| 410000 | 1869.6 | 56.57 |

| 420000 | 1860.5 | 57.41 |

| 430000 | 1851.4 | 58.26 |

| 440000 | 1842.5 | 59.11 |

| 450000 | 1833.7 | 59.96 |

| 460000 | 1825.0 | 60.82 |

| 470000 | 1816.5 | 61.69 |

| 480000 | 1808.0 | 62.55 |

| 490000 | 1799.7 | 63.42 |

| 500000 | 1791.5 | 64.30 |

| 510000 | 1783.4 | 65.18 |

| 520000 | 1775.5 | 66.06 |

| 530000 | 1767.6 | 66.95 |

| 540000 | 1759.8 | 67.84 |

| 550000 | 1752.1 | 68.73 |

| 560000 | 1744.6 | 69.63 |

| 570000 | 1737.1 | 70.53 |

| 580000 | 1729.7 | 71.44 |

| 590000 | 1722.4 | 72.35 |

| 600000 | 1715.3 | 73.26 |

| 610000 | 1708.2 | 74.18 |

| 620000 | 1701.1 | 75.10 |

| 630000 | 1694.2 | 76.03 |

| 640000 | 1687.4 | 76.96 |

| 650000 | 1680.6 | 77.89 |

| 660000 | 1673.9 | 78.83 |

| 670000 | 1667.3 | 79.77 |

| 680000 | 1660.8 | 80.71 |

| 690000 | 1654.3 | 81.66 |

| 700000 | 1648.0 | 82.61 |

| 710000 | 1641.7 | 83.56 |

| 720000 | 1635.4 | 84.52 |

| 730000 | 1629.3 | 85.48 |

| 740000 | 1623.2 | 86.45 |

| 750000 | 1617.2 | 87.42 |

| 760000 | 1611.2 | 88.39 |

| 770000 | 1605.3 | 89.37 |

| 780000 | 1599.5 | 90.35 |

| 790000 | 1593.7 | 91.33 |

| 800000 | 1588.0 | 92.32 |

| 810000 | 1582.4 | 93.31 |

| 820000 | 1576.8 | 94.31 |

| 830000 | 1571.3 | 95.30 |

| 840000 | 1565.8 | 96.31 |

| 850000 | 1560.4 | 97.31 |

| 860000 | 1555.0 | 98.32 |

| 870000 | 1549.7 | 99.33 |

| 880000 | 1544.5 | 100.35 |

| 885000 | 1541.9 | 100.86 |

| 890000 | 1539.3 | 101.37 |

| 900000 | 1534.2 | 102.39 |

| 910000 | 1529.1 | 103.41 |

| 920000 | 1524.0 | 104.44 |

| 930000 | 1519.1 | 105.47 |

| 940000 | 1514.1 | 106.51 |

| 950000 | 1509.2 | 107.55 |

| 960000 | 1504.4 | 108.59 |

| 970000 | 1499.6 | 109.64 |

| 980000 | 1494.8 | 110.69 |

| 990000 | 1490.1 | 111.74 |

| 1000000 | 1485.5 | 112.79 |

| 2 868 378 | 1008.910 | 6 hours |

| 8 140 000 | 635.4 | 24 hours |